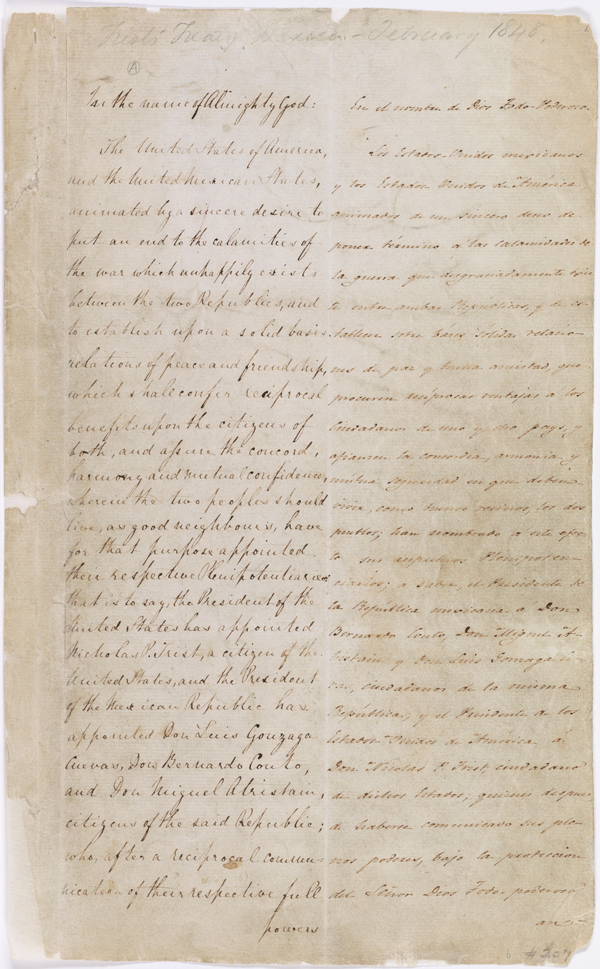

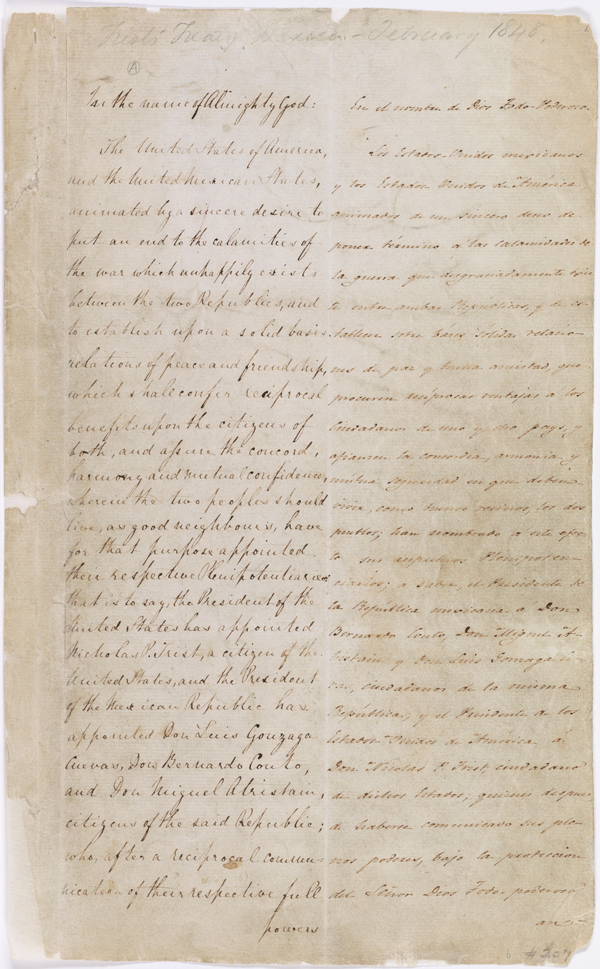

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, that brought an official end to the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), was signed on February 2, 1848, at Guadalupe Hidalgo, a city north of the capital where the Mexican government had fled with the advance of U.S. forces. By its terms, Mexico ceded 55 percent of its territory, including the present-day states California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. Mexico also relinquished all claims to Texas, and recognized the Rio Grande as the southern boundary with the United States. Read more.

Links go to DocsTeach, the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on DocsTeach asks students to read and analyze the treaty to explain the overall message and tone.

El Tratado de Guadalupe-Hidalgo (en Español) en DocsTeach requiere que los estudiantes lean y analizen el tratado para explicar el mensaje y el tono del mismo.

With the defeat of its army and the fall of the capital, Mexico City, in September 1847 the Mexican government surrendered to the United States and entered into negotiations to end the war. The peace talks were negotiated by Nicholas Trist, chief clerk of the State Department, who had accompanied General Winfield Scott as a diplomat and President Polk's representative. Trist and General Scott, after two previous unsuccessful attempts to negotiate a treaty with Santa Anna, determined that the only way to deal with Mexico was as a conquered enemy. Nicholas Trist negotiated with a special commission representing the collapsed government led by Don Bernardo Couto, Don Miguel Atristain, and Don Luis Gonzaga Cuevas of Mexico.

President Polk had recalled Trist under the belief that negotiations would be carried out with a Mexican delegation in Washington. In the six weeks it took to deliver Polk's message, Trist had received word that the Mexican government had named its special commission to negotiate. Against the president's recall, Trist determined that Washington did not understand the situation in Mexico and negotiated the peace treaty in defiance of the president. In a December 4, 1847, letter to his wife, he wrote, "Knowing it to be the very last chance and impressed with the dreadful consequences to our country which cannot fail to attend the loss of that chance, I decided today at noon to attempt to make a treaty; the decision is altogether my own."

Ignoring the president's recall command with the full knowledge that his defiance would cost him his career, Trist chose to adhere to his own principles and negotiate a treaty in violation of his instructions. His stand made him briefly a very controversial figure in the United States.

Under the terms of the treaty negotiated by Trist, Mexico ceded to the United States Upper California and New Mexico. This was known as the Mexican Cession and included present-day Arizona and New Mexico and parts of Utah, Nevada, and Colorado (see Article V of the treaty). Mexico also relinquished all claims to Texas and recognized the Rio Grande as the southern boundary with the United States (see Article V).

The United States paid Mexico $15,000,000 "in consideration of the extension acquired by the boundaries of the United States" (see Article XII of the treaty) and agreed to pay American citizens debts owed to them by the Mexican government (see Article XV). Other provisions included protection of property and civil rights of Mexican nationals living within the new boundaries of the United States (see Articles VIII and IX), the promise of the United States to police its boundaries (see Article XI), and compulsory arbitration of future disputes between the two countries (see Article XXI).

Trist sent a copy to Washington by the fastest means available, forcing Polk to decide whether or not to repudiate the highly satisfactory handiwork of his discredited subordinate. Polk chose to forward the treaty to the Senate. When the Senate reluctantly ratified the treaty (by a vote of 34 to 14) on March 10, 1848, it deleted Article X guaranteeing the protection of Mexican land grants. Following the ratification, U.S. troops were removed from the Mexican capital.

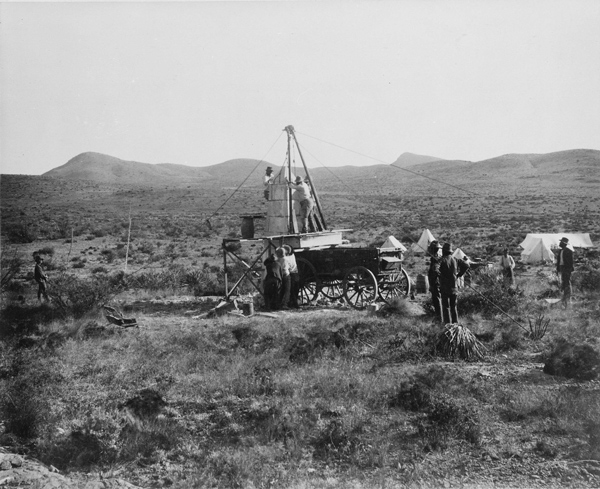

To carry the treaty into effect, commissioner Colonel Jon Weller and surveyor Andrew Grey were appointed by the U.S. Government, and General Pedro Conde and Sr. Jose Illarregui were appointed by the Mexican government, to survey and set the boundary. A subsequent treaty, the Gadsen Purchase, of December 30, 1853, altered the border from the initial one by adding 47 more boundary markers to the original six. Of the 53 markers, the majority were rude piles of stones; a few were of durable character with proper inscriptions.

As time passed, it became difficult to determine the exact location of the markers, with both countries claiming the originals had been moved or destroyed. To solve the problem, a convention between the two countries was concluded in the 1880s; and a survey was done that verified the need for definite demarcation of the boundary. The International Boundary Commission was created to relocate the monuments and mark the boundary line. The U.S. commissioners employed a survey photographer to record various views of each monument located and erected by the U.S. Section.

This text was adapted from an article written by Tom Gray, a teacher at DeRuyter Central Middle School in DeRuyter, NY.

Materials created by the National Archives and Records Administration are in the public domain.